|

|

Post by Dave on Jun 21, 2012 20:07:01 GMT -5

Before we leave the topic of music … and we probably won't stay away for very long … I'll mention that if you haven't had enough of Dave's Musical Memories, there's another more serious version (but not much more) of My Life As A Musician that covers later exploits in the band and makes the following observation: My desire to be noticed by girls as I played in the band (in college) didn't work out quite the way I had planned. Still, playing to rowdy young women was a lot of fun. I'm reminded of that when I occasionally sit in church while the music ministry sing their hearts out or play the guitar or kazoos at a Folk Mass. I assume they are enjoying themselves, but with no young women screaming when you huff out your low notes, I can't imagine singing in the choir is as much fun as belting out a song to dozens of beer drinking sorority girls.

The story is at: www.windsweptpress.com/musician.pdf |

|

|

|

Post by Dave on Jun 22, 2012 7:28:54 GMT -5

My world up through the end of third grade was Cornhill on the block of Taylor Avenue between Square and Leah. Here's what it looks like today. I lived upstairs in the house under the red star. I've penciled in the railroad, street names, the cemetery, etc.  There was a lot to do in my neighborhood. Perhaps I should qualify that by saying "a lot" for the 1940's and early 1950's. Hanging out at a neighborhood store might have been the highlight of a kid's life back then. In the four blocks between James and Eagle Streets you'd find probably 2 neighborhood stores on every other avenue. We had a refrigerator, and my father shopped weekly at the A&P just south of the Olbiston on Genesee Street. But many of our neighbors didn't even own an ice box (ice was still being delivered for those who relied on it). They shopped daily at the corner store. Far from the Convenience Stores of today, the corner store usually stocked everything you needed to survive. The convenience of a corner store, and one way of looking at it, was the store owner stored your food for you. He also let you pay for it as you needed it, or would run a tab for you. Paying your bill was usually done when you got your week's wages on Friday . Our local grocery was Walter's, on the southeast corner of Taylor and Leah, just across from the Villa Restaurant. Mr. Walters, we all called him, had come from eastern Europe and married an American woman. He was by trade a butcher and one side of his store held a huge blood stained wooden block, all of his cleavers and a not very cold refrigerated display case filled with meats. Cans of vegetables lined the opposite wall, and early each morning Mr. Walter got in his 1929 Ford and drove down to a Farmer's Market near Union Station for fresh vegetables. By 9:00 a.m., we could hear the car putt-putting up from Eagle Street and we'd run down to the corner to see Mr. Walters unload the back rumble seat stuffed with greens and fruits. He sold penny candy too. When we bought a Coke or Pepsi on a hot summer day, we paid him seven cents and got two back when we returned the bottle. We always took the two cents in candy. He'd get red in the face if you asked for your two pennies back. I did, once. I don't remember why. He called my mother up on the phone and said I was being a little smartass. Smartass said with a heavy Prussian accent sounded like a compliment to Mom, so she said, "Thank You, yes, he's a nice boy," and Mr. Walters hung up. |

|

|

|

Post by Dave on Jun 22, 2012 13:06:33 GMT -5

Mr. and Mrs. Walters brought up 3 or 4 daughters in the tiny apartment behind the store. I remember only the youngest, aged about 13 or 14 years and nicknamed Mikey. When I was 3 or 4 years old, she used to swing me through the air by the hands until I laughed myself silly. She was a redhead and easy to spot. If I saw her down the street, I'd run down the sidewalk as fast as my chubby little legs would carry me. So even back then I was chasing redheads. My wife is a redhead and I wouldn't have chosen anyone else. But I don't recommend them to the faint-hearted. What Mikey grew up to be like, I really don't know. I saw her at Blessed Sacrament church ten or more years later when I was a teenager, but only said Hello to her. And to her Mom as well, who didn't in the least mind being called "Mrs. Walters." I never did learn their last name, so I had to make it up when I wrote the following story. There's some embellishment, but I think it captures all the characters well enough. DistractedWhen I was seven years old there were three dogs named Lassie in our neighborhood. Well .. OK … maybe only two at the same time. The first Lassie was run over by the Salvation Army truck that came to pick up Mr. O’Reilly’s furniture after he died of Malaria. In truth he probably died of a heart attack or some disease we kids couldn’t pronounce (like acute ethanol toxicity or late stage cirrhosis.) But we did know how to say Malaria and our young minds needed drama to balance the unbelievable fact of death, even a death from old age. Drama may be why we believed Mr. Belcher was eaten by a tiger in Mexico and why Mrs. Lambertini was rubbed out by the mob. Lassie was a popular dog name because of the famous canine movie star. Rin Tin Tin was also a famous movie star, but I never heard of anyone in our neighborhood calling their dog Rin Tin Tin. Or even Rinty, that particular dog star’s nickname. How Rin Tin Tin came to have his name in the first place was a mystery to me. I asked Mr. Banasznewski who ran a butcher shop where I was often sent on errands by my mother. “Who would name a dog Rin Tin Tin?” I asked of the man. “Only a Chinaman,” he replied. “You think Rin Tin Tin is Chinese?” I asked, aware that the dog certainly looked like a German Shepherd. “His name could be Chinese,” said the butcher, distracted by a long drive to left field that he was just hearing about on the radio that played constantly on the shelf above his blood-stained butcher block. “Look at all the letters in Rin Tin Tin,” he added. “Doesn’t Banasznewski have more letters?” I asked. “Maybe so,” he replied, “but they’re not separated into three words that rhyme … Rin, Tin and Tin.” “Why would a German shepherd have a Chinese name,” I asked Mr. Banasznewski, the butcher. “International trade,” said Mr. Banasznewski. He turned the volume on the radio up another notch and then added, “The Germans and the Chinese exchange tea and … strudel.” You could hear the crowd roar over the radio now as a line drive shot out away from the batter toward second base. I sensed Mr. Banasznewski was no longer fully involved in our conversation. “This is from my mother,” I said and held out a folded slip of paper. He turned from the radio immediately and stepped over to me. Taking the note, he raised it to his face while pushing his rimless eyeglasses up on his forehead. His brows furrowed as he squinted to read my mother’s handwriting. A smile now grew on his face and he looked up at the ceiling, as if enjoying a private reverie. Then he turned and bent over his butcher block. From the upper part of his apron I could see him pull out a black grease pencil and he used it to write on the back of the paper I had given him. Then he handed the note back to me. I’m not supposed to read other people’s notes, but I could see his answer in big block letters, two of them. “No,” was all it said. Arriving home, I found my mother in the kitchen listening to our small radio that was tuned to the soap opera, “Young Doctor Malone.” “If a dog’s name has three parts that rhyme,” I said to her, “is there a chance he’s Chinese?” She smiled at me and said, “Why would you think so, darlin’?” “Mr. Banasznewski said so,” I replied as I watched her reach across the kitchen cupboard and turn up the radio. An organ blared from the speaker and a voice droned on above the music to bring us up to date on how many women were in love with Young Dr. Malone. I held out the square of paper. “Here’s his answer to your note.” Her eyes widened a little as she took the slip of paper from me and read the butcher’s message, “No.” A look of concern came over her face and she said aloud, “What was the matter with her?” “Her?” I asked. “Aunt Lydia,” came the reply. My mother’s sister, Lydia, worked at the butcher shop. Mom handed back the note. It read: “Darlin’, can you come over tonight?” I handed the note back to Mom. “Was the note for her?” I asked. But seemingly more concerned with Young Doctor Malone’s admirers, my mother didn’t answer. Staring at the radio, she absent mindedly placed the note into the drawer in which we kept bottle openers and soup ladles. Dad found the note that night before he went out to his bowling league. Young Doctor Malone was now performing an emergency appendectomy on a woman he had met the day before in the hospital cafeteria. Did Mom tell me who the note was for? Did I see Aunt Lydia at the butcher shop? I didn’t remember. I was still trying to figure out why someone would name their dog Rin Tin Tin. And by the way, what’s a strudel? From the book, "Nowhere," copyright 2011, David Griffin  |

|

|

|

Post by Dave on Jun 23, 2012 6:13:09 GMT -5

Children's War

Directly behind the upstairs flat we rented on Taylor Ave. was an open field that seemed huge when I was a kid. Our favorite game to play back then was War. Not the card game, but the playtime activity where all the kids we didn't like were forced to play the parts of Japanese infantryman, while the future A-type personalities grabbed the roles normally reserved for actors like John Wayne. There were a few kids who enjoyed playing the Japanese, believe it or not, because they wanted to grow up to be what they heard Japanese soldiers were like, ferocious killers. Many of these kids would never get through high school because they were always in fights. A couple of these boys reached age 18 as the Korean War was starting in 1950 and became neighborhood heroes by going off to fight the Red Chinese. Their names were celebrated as they went off to war on the train one bright and crisp autumn morning, and when they came home from some numbered hill on the Korean peninsula late the following winter in body bags.

I remember being not the smallest in the group, but not far up the ladder from the youngest kid at the bottom. Other more aggressive boys grabbed all the good roles first. Only corporals and sergeants and Captains seemed to play. I never remember anyone wanting to be a PFC. Most boys preferred to carry a fake gun and shoot everyone else, run out of bullets and proceed to hit friend and foe alike with their weapon. My favorite activity was talking, so I wasn't very good on the battlefield. I probably would have made a great make-believe JAG, had any of the many Captains requested one. I was known to speak up when I saw anything amiss on the killing ground. Broken rules always bothered me, so maybe I functioned best as a Junior Battlefield Referee.

"You can't win this skirmish," I told an older kid who was gleefully shouting made-up Japanese words as he chased around a boy my age who wore his uncle's World War II helmet and carried a garden shovel with the handle sticking forward that was supposed to be a machine gun.

"Why not?" spit back the 12 year old, who said he was Colonel Satchmo Hiyakawa of the Imperial Japanese Army

.

"Well, first of all," I replied, " 'Satchmo' is not a real Japanese name, and second, you're beating up John Wayne and he can't lose a battle."

"I'm John Wayne," the younger kid shouted from under his helmet. "I'm John Wayne!"

"Well, excuse me all to hell and back," said Satchmo. And with that he grabbed the shovel from the boy and brought it down hard on his helmet.

We took Captain John Wayne Nysynski to his mother, blood streaming down from somewhere up in his helmet and mixing with copious tears and bad language. She laid her boy out on the kitchen table, pulled his helmet off and discovered a wound that wasn't too serious.

While Mrs. Nysynski worked on her son's head, now neatly resting in a copper-bottom Revere Ware fry pan to contain the blood, we boys stood in her kitchen and passed verbal status messages along to the tens of kids beginning to congregate on the back stairs. The entire neighborhood always showed up for blood.

Behind me, Bobby Talerico piped up.

"Mrs. Nysynski, do you think he'll live?"

"Till his father gets home," she said. "After that there's no guarantee."

I was impressed with her using the kitchen table as a stretcher. My mother would have never done that. It might have ruined the place mats.

|

|

|

|

Post by Dave on Jun 23, 2012 8:47:54 GMT -5

OK, I'll admit it. In addition to a Cornhill Boyhood, there was also a Girlhood. Here are some of the young ladies who hung around Roosevelt School in the 1500 block between Taylor and Brinckerhoff Avenues in 1950. Click once or twice to enlarge.  |

|

|

|

Post by Dave on Jun 23, 2012 17:27:11 GMT -5

My mother was a great girl. We three boys didn't get away with much around her when we were younger, but as we grew into our teens she allowed us to charm her out of making us take care of chores that she secretly preferred to do herself. Born in 1913, her mother died in 1920 during a still birth. Grandpa put Mom in a boarding house during the week, where she met a young woman who would become her step mother. I remember when Grandma came to live with us (see A Trip To The Zoo, above) and it was sometimes hard to tell if the two women were mother and daughter or girl friends. I don't think they could have sorted it out. I have an image in my mind of the two sitting at the kitchen table shelling peas or peeling potatoes, giggling like girls as one read a letter from a cousin in Fulton who was a born comic married to an old sourpuss. Years later, when Cousin Mabel was 72, her Old Sourpus died and she took up with a colorful man she met in a Syracuse shopping mall as he sat painting small portraits for $1.99.

Mabel's new man had no house and hardly any middle class values of the type that would keep one running in place at the insurance agency every day until you died of boredom. He was educated at Dartmouth, although few knew it until his funeral. Arthur was simply like Charlie Chaplin, not born for these Modern Times. He lived for art, and though he was evidently not a terrific craftsman, he loved it anyway.

Arthur had an old car and no house. He sold his car. Mabel sold her place in Fulton across the road from the Oswego River and together they took off. They lived a spartan life from a motor home, painting small portraits together between Fulton and Florida for the next 13 years. Mabel had never been so happy. A former piano teacher, she once told my mother that as she sat at her piano with a student in her dining room on West First Street North (I didn’t make that up) in Fulton as a young mother, she felt dead, stuck, and half buried. She never imagined she would one day live on the road like a circus performer and go out to dinner in the evening if they sold enough paintings. She was absolutely convinced God loved her, and she didn't complain he had taken his time getting around to giving her a wonderful life.

My mother admired Mabel, but did not have the courage or self esteem to ever attempt what Mom thought was a crazy way to live. She and my father stayed put. And dealt with feeling stuck, dead, and half buried sometimes.

|

|

|

|

Post by Dave on Jun 24, 2012 8:42:44 GMT -5

Mom's method of disciplining her children was quite straightforward. If you pissed her off, she came after you with a large spaghetti spoon. One whack of that on your backside and you were willing to consider alternative behaviors. You could argue about the advisability of striking a child with a steel shanked pasta tool, but you'd have to argue with Mom and I wouldn't advise it. To my knowledge, her three sons grew up to take care of themselves and were seldom intimidated by any woman, unless she was carrying a spaghetti spoon.

Mom And The U.S. Constitution

I was musing the other night on crime and punishment and freedom. I often think deeply on issues in which I have no expertise and feel quite satisfied when I solve any of humanity’s crucial problems.

I read of a prisoner’s case brought against the government for cruel punishment. I think a prisoner’s rights are related to my personal freedoms, because the government's sway over both of us is limited by similar law. Damage to his rights could eventually lead to a weakening of mine. So, the proper administration of justice is important to all of us.

Probably the most effective person I knew when it came to punishment was Mom. Her personal attention to my boyhood faults and her precise judgments were executed from a base of love, but they clearly trampled on my civil rights. She could not have cared less.

Mom would have no problem running a prison. She knew how to call 'em and she knew what you were thinking and she knew what hurt and what didn't and she didn't give a rat's ass if your best friend Tommy got away with murder. But if you said "rat's ass," you got another night of jail at home with no TV.

As I grew toward puberty and asked Mom who gave her the authority to Lord it over me, her answer snapped back without hesitation. "GOD anointed me. Now go clean up your room!" At age twelve I was almost as tall as the little woman. When I offered to arm wrestle her to determine if it was really my turn to do the dishes, she accepted. And won.

The United States Constitution would not allow my mother’s brand of punishment to violate an inmate’s human rights. Mom might do a great job running the State Prison, but she would eventually spend all her time in court defending herself against civil rights suits.

The Constitution also serves to prevent the practice of Mom-ism outside prison walls by those who want to control us as though we were children. Laws said to protect us continue to whittle away our freedoms. Rights are demoted to privileges and whatever is dangerous becomes licensed. We see this over-protective attitude in the public sphere’s fixation on safety and security. Often the new laws and regulations seem very practical.

But that's the great thing about America. Sometimes we’re willing to replace practical wisdom with impractical abstractions, because without an impractical idea like freedom our personal abilities could not unlock our promise. We wouldn’t live up to our potential nor mature as a nation.

My mother knew when to stop acting like a Mom. It was probably difficult for her. Allowing me to follow my own paths as I grew up may have seemed impractical to her at times. But she knew I would in some ways be rid of her in the future, as she had grown beyond her parents. I would build a worthwhile life based on my freedom rather than another person's wisdom, even it was hers. .

The power Mom wielded over me as a child was long ago replaced by a mutual respect, built brick by brick while I advanced to maturity. Mom became important to me as a person and not as a set of rules. I was free to do as I pleased, to enjoy the fruits or accept the consequences of my actions. She might have continued to insist I obey her, but she was smart enough to know that seldom succeeded. Instead she let the reins slacken a little at a time while she rode herd on my adolescence and I galloped toward my independence. I arrived there certainly not without her help, but without her holding my hand. But I suppose that’s just a son’s opinion.

From "Big Ideas," copyright 2012, David Griffin

|

|

|

|

Post by Dave on Jun 24, 2012 14:07:49 GMT -5

My mother was quite loyal to her husband, my father, although sometimes to a degree that made you wonder if she had her head screwed on or had left it at a Bingo game. Not to worry. She was more than she often appeared.

Advice

There is such a thing as duty, of course, and it is sometimes conditional. But family .... that is never conditional. We stick with each other even when it might not be a good idea to do so.

I remember at age nine sitting at the kitchen table doing homework while my mother peeled potatoes and my father fooled with a lamp he was trying to get working again. Mom asked my father, "Who should I vote for, Jack?"

"Stevenson," he said, "a Democrat is always the working man's friend."

"But I like Ike," she said. "He looks like a President."

"I suppose so," said my father, "but what about Father O'Brien, Mary? He likes Stevenson."

"The priests always like Democrats," she said. "Something fishy there."

"That's sacrilegious, Mary," he said.

My mother didn't respond. A proper Irish Catholic woman in 1952 did not play against the Catholic trump card, not in our neighborhood.

"What about the bomb?" she said.

"What bomb?" asked my father.

"The Atomic Bomb," she said.

"What about the Atomic Bomb?" he inquired.

"Well, " said my mother, "Ike is a military man. He'd know how to stop one."

"Now, just how would Ike stop an Atomic Bomb, Mary," said my father, exasperated.

"I don't know," she said, "and it's probably a military secret."

"Uh huh," said my father.

"Just how do you think Father O'Brien would stop a bomb?" she asked.

"Father O'Brien is a priest," said my father with some emphasis, he doesn't have to know how to stop a bomb!"

"Well, I'm talking about if it lands here in Cornhill," she said, heat now rising in her voice. "After all, Ike can't be everywhere! Father O'Brien is always in some gin mill ....

"Mary!" interjected my father.

".... do you think Stevenson is going to come to this town and stop an Atomic Bomb?" she ended with a flourish.

My father was quiet for a moment as he stared up at the ceiling, grinding his teeth

.

"I think," he said finally, "you should vote for Ike."

"No!" she shouted, slamming the potato peeler down on the table. "I will vote with my husband," she said. "I'll vote for Stevenson."

My father made a good decision. He got up and left the kitchen.

David Griffin copyright 2011

|

|

|

|

Post by Dave on Jun 24, 2012 19:13:03 GMT -5

Before we leave Mom, I have one more story to tell. How To FlirtWho teaches a boy from a mostly male family to recognize when a girl is flirting with him? Certainly no one stepped forward to do the job in my family in the 1950’s. My father was probably genetically oblivious to what women signaled to him. Males ran in our Irish family and possibly we had a surfeit of Y chromosomes. We were never tuned into the opposite sex. A college roommate had to explain to me long ago that the girl who would become my wife was interested in me. I don’t know how he could tell. I couldn’t. And it was hard for me to believe my mother knew how to flirt. Don’t ask me why. I just know Mom wasn’t capable of flirting. Maybe it’s because I never saw her do it. But I have to admit I have a vague recollection of her getting lovey with my father … in a proper Catholic way, of course … just before I would run out the back door screaming, “Someone stop my parents from doing that!” I never asked how Mom and Dad got together back when they were young, but I always wondered if well meaning friends pulled their clothes off and pushed the two into a closet at a wild New Years Eve party. We Irish are not always subtle. I remember a sweet girl named Alice in the 9th grade and I was terrifically obsessed with her one summer after seeing her in a bathing suit. I had no idea what lie beneath the bathing suit, but twenty billion years of evolution guaranteed I didn’t need to know in order to want it. In the spirit of first things first, I longed to know if Alice was interested in me. I could not tell. On the city bus one afternoon, I heard a young woman say to another, “Oh, you can tell when he’s interested. A girl can tell.” “So can a boy,” said her seatmate. That was news to me. I thought I was a fairly good looking fourteen year old guy and someone might agree, but I just didn’t know how to read the signals. I don’t know what most teenage boys did when stumped for an answer, but I always turned to our local library. Although you wouldn’t think so, in those hallowed halls I discovered how to build an explosive device big enough to blow up my brother’s bicycle and even how to properly call in the resulting fire in a concise and professional manner. Of course, the best answer always depended upon how well you formed the question. “Can you recommend a book on flirting?” I asked the elderly librarian the next morning. “You should talk to your mother,” said the woman. “She’s busy,” I said. “Besides, I don’t want to flirt with anyone, I want to do a scholarly study on the subject.” This last phrase always goes over well with librarians. They get all gooey and helpful when they hear it. A half hour later the woman stopped and sat at the table where I had piled up a number of books, mostly psychology tomes and journals. Not very far in my quest, I was skimming an article on the socio-sexual aspects of dimorphism among apes and its effects on food gathering. “To be honest,” I admitted to the nice lady, “all I wanted to know was how to tell if a girl was interested in me.” “Isn’t it really quite simple?"she said. "Normally, the girl would catch your eye first.” “I don’t look girls in the eye,” I said. “And then she might smile at you,” the woman continued. “But maybe she’s smiling because she forgot her lunch money and wants to borrow a dollar,” I replied. “I don’t want to be taken advantage of, not by a girl Juh-GO-low.” ”That’s Gigolo,” said the librarian. She smiled sweetly, stood up and left. Back among the shelves I stumbled across an anthropological classic, “Female Courting Signals Among Primates” (or something like that) and finally found the mother lode of flirting tips. Point by point, the book explained each gesture a girl may use to indicate interest in a boy. Sure, the young lady may not realize what she’s doing, but a budding 14 year old anthropologist like myself should be on the watch for these signs. Here they are. She sticks out her chest at you. This is for the purpose of showing she’s ready to nurse … a baby, I guess. Boy! I’d never had a girl do that to me, except for the night at the skating rink a buxom lass lost her balance and came flying into me. Her chest was all she had to protect herself, of course. So, does that count? She looks at you and plays with her hair using her finger or a pencil. This is called preening. Yes, Skeevie Eevie did that across the room to me in 4th grade, but she was itching terribly, her eyes were unfocused and everyone said she had bugs in her hair. She touches you somewhere safe, the forearm as an example. This is the female testing if you are comfortable with her. By age fourteen, not a single girl had ever reached out and touched my forearm. Older women had taken my arm to cross the street when I was downtown, but I don’t think they were trying to pick me up. She lets her wrist go limp. Bent over, it’s a sign of submission. Oh! I didn’t know that. I thought it was a sign she was a girl. A real surprise awaited me when I opened the next book, “How To Tell What A Woman Really Wants.” “Women will tend to use a lot of subtle cues to entice you,” it announced, “but you have to be absolutely sure you understand what she is saying with her body.” Uh, if I were sure, I wouldn’t be looking it up in the library. The book, written by a Reverend Hiram Percy, never specifically told me what a woman really wanted. Perhaps the Reverend had to finish the book on a deadline or maybe there would be a sequel. In any event, it may have been written for the older crowd I saw dancing and kissing at Uncle Harry’s last New Years Eve Party. You’re not going to believe this, but after I boarded the city bus for home, Alice got on at the next stop and sat in the sideways seat up front. She was so lovely in profile. I kept furtively glancing up from my shoes to look at her, waiting for the girl to catch my eye, smile, flip her hair or stick out her chest. She appeared to do none of these, but underneath her extra roomy Catholic School uniform all kinds of things might have been going on without my noticing. I realized she would never send any of these signals without knowing I was just down the aisle from her, so I began to make noticeable arm movements that could be otherwise explained if I embarrassed myself. “How long has it been since you showered, young man?” asked the elderly lady beside me. I kept swinging my arms. “It’s a mental rehearsal for my hoop shot,” I told the old woman. When I glanced back toward the front of the bus, Alice was staring at me, incredulous. She got off at the next stop, five blocks before her street. Dejected, I made my way home, thinking I would have to face the inevitable. I’d have to ask Mom. My mother stood in the kitchen at the stove, wrapped in her favorite apron, the one that looked like she was getting ready to feed the entire Third Army. I could not bring myself to believe this woman knew how to flirt, but I was out of options. ”Mom,” I began, “how can I tell if girls are interested in me.” “They’re not. You’re too young,” she said. “Well, I want to be prepared, just in case,” I said. “How does a girl flirt?” Mom left the stove and walked over to stand in front of me as I sat sideways in the chair at the kitchen table. She reached out and grabbed my ears and pulled my face into her aproned bosom and quickly wrapped her arms around me in a headlock, smothering me in a place I’d have loved to be if it belonged to a girl my age. She planted a kiss on my forehead and roughly shoved me back in my chair. “If a girl does that to you,” she said, “you send her to me." I’ve been married 47 years and I’m still waiting for a girl my own age to do that to me. From the book, "Big Ideas," copyright 2012, David Griffin |

|

|

|

Post by Dave on Jun 25, 2012 8:00:48 GMT -5

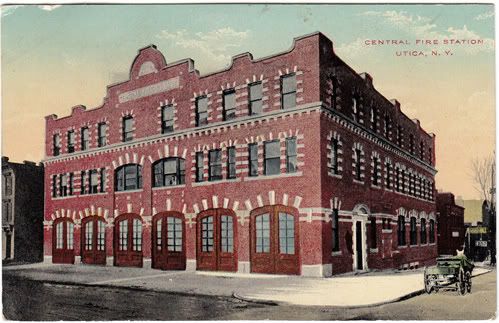

Above, old UFD headquarters on Elizabeth Street. Built around 1912, obliterating the Post Street African American population. Above, old UFD headquarters on Elizabeth Street. Built around 1912, obliterating the Post Street African American population.My Dad was a pressman for the Observer Dispatch. He had begun work while in high school for the OD, then left for the Utica Fire Department when he saw more opportunity there, and probably the excitement he would never admit he sought. Eventually, he returned to the newspaper. |

|

|

|

Post by Dave on Jun 25, 2012 8:23:57 GMT -5

I met a woman on another forum who believes this is a photo of her Dad, but he looks like my father, too. She could be right, however, because I'm not sure his ladder truck crew worked on hoses, although the entire crew may have pitched in after the fire. I met a woman on another forum who believes this is a photo of her Dad, but he looks like my father, too. She could be right, however, because I'm not sure his ladder truck crew worked on hoses, although the entire crew may have pitched in after the fire.Taller buildings needed longer ladders and these were carried by a ladder truck towing a trailer. The ladders could be those that were removed from the trailer and put against the building, or the kind built into the truck that extended up to a great height. When the length got too long, a steerable rear axle on the truck trailer was needed to get around corners. Dad was a tillerman at No. 2 Engine on Elizabeth Street, the central headquarters building the UFD built just prior to World War I. The tillerman was the guy who sat up back on the long ladder truck and steered in the opposite direction so the vehicle could turn on to a street without the rear wheels running over the curb or a stop sign or a pedestrian standing there daydreaming. Here's a good webpage explaining the operation of a rear tiller ladder truck. My Dad's truck was much older and there was a tillerman seat, but no small cab. report-on-conditions.blogspot.com/2010/07/best-seat-out-of-house.htmlHere's a tillerman up on the back of a really old ladder truck.  Seen from the ground, tillerman seat of roughly my father's era.  A more modern view of a tillerman, but without an enclosure cab.  An enclosed tillerman cab. Nice accessory for winter.  |

|

|

|

Post by Dave on Jun 25, 2012 17:47:54 GMT -5

I was quite young at the time Dad was in UFD and probably remember more of his spoken memories than my own unique memories of his fire house days. One abiding image stands out, however. On a summer night my mother took me downtown on the Eagle Street Bus from Cornhill. We got on at Square Street and Taylor and off at Grace Church, then walked over past Charlotte Street to the firehouse. When we arrived, Dad was seated with other men on two benches outside an open bay door, enjoying the early evening air. As we reached the group, all the other men stood and left so that Mom and Dad had some degree privacy (sitting on a bench on Elizabeth Street!) I was told later this was the protocol the men observed to afford each other at least a little privacy. Dad's schedule was (I think) three 24-hour days on duty and two or three off. Fireman arrived at the beginning of their 3 day shift and were served dinner by the shift going off. They then put together a three day menu, estimated the cost of groceries, divided it up and sent a volunteer with the money to buy supplies for their shift. On his shift, my father always volunteered to shop because he liked food shopping and was the main food shopper in our family until he became too elderly to leave his apartment. During the war, each fireman contributed his share of the necessary ration cards for meat, sugar and other rationed items. Dad would hand over the ration stamps at the store, but most often the clerk noted his UFD uniform and gave the coupons back to him. Later at the firehouse, many of the men wouldn't take them back. "You have young children, John," they said, "you keep 'em." Dad didn't need them, because Gram and Grandpa gave him half of their meat coupons and no one could afford sugar very often. So he gave the coupons to other relatives and neighbors.  A good way to start an argument among older folks years ago was to state that rationing wasn't really necessary in WW II, but President Roosevelt insisted on it to drive home the point to the American people that we were at war. Those who had brothers and sons in combat said they had no need for another reminder. There's a terrific web page on WW II rationing at: www.ameshistoricalsociety.org/exhibits/events/rationing.htm |

|

|

|

Post by Dave on Jun 25, 2012 17:51:03 GMT -5

Dad enjoyed fighting the fire each time he managed to get the rear end of the ladder truck safely to the burning structure. Firemen love to show off. Most fires took the crew of No. 2 Engine along Genesee Street downtown. Dad said he noticed the fire engine drivers would sometimes take that route even if another way was faster, just to show off to the crowds near the Busy Corner. There would be Dad, up on the back of the truck and leaning forward over the tiller wheel, his solid chest braced against the wind as it whipped his open turnout coat back over the seat. Racing up Genesee Street or any other road, by the time the crew got to the fire, they were quite excited, he said. I can believe it, having been a volunteer fireman years ago. Jumping off the trucks, the crew was ready to save anyone in sight and to quench the fire. They were met by the Chief and his assistant traveling separately in the Chief's car (no doubt so the two could get there first.) The Chief's job was to assess the fire and quickly plan an attack. The assistant's job was to collar all the firemen and stop them from jumping in feet first. There were too many instances of a pumped up fireman taking his axe and chopping down the front door of a residence before checking to see if it was locked. And once a resident was almost chopped down, but got away with just a bad cut. Firefighting is dangerous work and it always has been. Luckily, the UFD has a estimable safety record, for both the firefighters and fire victims. I have to believe it got started after the famous Crouse Block fire on Broad Street in 1897. Two Firemen, Isaac Monroe and John O'Hanlon, were killed when the burning building collapsed on them. They've been immortalized by the locally famous Fireman monument in St. Agnes Cemetery. O'Hanlon had been cited for bravery in the Genesee Flats (later the Olbiston) Fire just a few years before. When the monument was installed at the Mohawk Street cemetery, my great grandfather, Patrick, was listed with UFD's First Division in the news article about the well attended ceremony. His membership would have been largely ceremonial by 1898, given his age, but with good reason since he had been one of the early organizers of Utica's city-wide fire department. You can view the portion of the thread about Firefighters O'Hanlon and Monroe here on Clipper's Busy Corner in the " Olbiston/Genesee Flats History" thread, starting around page 30. It's followed by posts about the Olbiston, and then the Crouse block story, as told by the 1897 newspapers, resumes toward the bottom of page 33. Here's the link to page 30 of that thread: clipper220.proboards.com/index.cgi?board=musingsandchildhoodmemories&action=display&thread=2238&page=30Here's a photo of the monument in St. Agnes Cemetery.  |

|

|

|

Post by Dave on Jun 25, 2012 22:48:25 GMT -5

Here's a Utica Boyhood story. William Foley was delivering newspapers on March 3, 1893 when the Genesee Flats burned down. He is credited with turning in the general fire alarm after the fire company first on the scene misjudged the severity of the fire and did not call for help. The apartment house burnt to the ground and four lives were lost.

The building was replaced by one similar in appearance, The Olbiston. Two significant changes were made to the newer design. First, the Olbiston had separate cellars so that a fire would not spread as easily. Second, the Olbiston was five stories high, two less than the Genesee Flats, so that escape ladders would reach more of the residents.

My story is a fictional account of what Billy Foley may have seen and experienced. It is based on a significant amount of old newspaper research conducted by the late Jon Hynes, Fiona and myself.

Billy Foley’s Morning

It’s just so peaceful in the morning. No one is out and about, and all I ever hear are the trains and factories running all night over on the west side, out Whitesboro Street. And in the winter, the swish of tire rims when a hack is pulled past by a weary horse. And, you know, me and Da need the money, so before school I run down to the Herald and get me a bag of papers and sign the slip to pay tomorrow and take the whole shebang up Genesee Street, selling the news to whoever will give me a couple of pennies for the paper. I bring home the coins to Da and he counts them out and gives me the money that’ll go to the Herald next day. He always has me put it in the old teapot on the window sill for tomorrow.

It’s been a cold winter and if Da didn’t drag me out of bed in the morning, I wouldn’t be out there slogging through the slush and snow, I can tell you. And, Jesus, I got a welt on the back of my shoulders from Brother Barnabas at the ‘cademy, and he keeps hitting me there every time I fall asleep reading the catty-kism.

I most often sell all the papers by the time I get to the court house, so I don’t always get up to Genesee Hill. But that morning it was freezing and not many people were on the streets. So I walked all the way to the fountain at Oneida Square, and by that time I could smell the smoke. Then all hell broke loose as the team of horses and men from the No. 1 fire company came pounding by me and headed up Genesee Street. Holy Cripes, a real fire engine! I threw down the rest of the papers and I ran like the dickens to catch up. By the time I got to the Genesee Flats, the people were trying to get off the front of the place from the balconies. Seven stories of apartments makes for a lot of people.

I’m thinking I wish I’d gone home instead. Nobody should ever have to see people dying like that. I still have dreams about it. Yeah, I know … but that poor lady. I heard her head crack open. Sometimes when I’m dozing off in school, I’ll hear that crack and my stomach will get queasy if it’s just before lunch.

I’m a good reader, and I’ve read everything in the papers about the fire, at least in the Herald, because that’s the paper I sell. From what’s in print, you’d think everyone in The Flats got called on by the management and politely told about the fire, and pretty please just get dressed and meet across the street for tea. But that’s not what happened. Or if it did, it’s only because nobody seemed to know whether they were dealing with a big fire or a small one. Not even the firemen.

|

|

|

|

Post by Dave on Jun 25, 2012 22:51:12 GMT -5

I came up to the building, all I saw were firemen in the lantern lights. They were scurrying around and they didn’t look like nobody had told them the fire was right in front of them and they should be doing something about it. I didn’t see any flames, not at first. But what I heard was awful, people screaming and crying and yelling for help. I think I got a little rattled, and wondered where the hell the voices were coming from. It was dark and there was smoke everywhere. For a second, I wondered if all the voices were up in the trees. Then a trunk of clothes crashed down and split open about ten feet from where I was standing. Just dropped right out of the sky! I looked up and saw coats and shoes and a lady’s dress floating down at me. They must’ve been trying to save their belongings. And then, over at the far end, I saw a man dangling on what looked like a string of sheets or clothing. I had to laugh, thinking it was funny. I wanted to shout at the folks to go back inside. There weren’t any flames. I thought this would be just a smoker … like maybe someone’s couch was burning and they’d haul it out in the snow in a few minutes, and everyone could have a good laugh and go back to bed.

It was getting lighter now, and people were still crawling down from the balconies like they were a circus troupe. Some were wailing and shouting and trying to find each other. One lady kept grabbing me and asking if I’d seen her brother. She must’ve asked me ten times. It shook me, and made me afraid again. Oh, those poor people hanging from the windows and balconies.

The smoke was awful smelling, not like a campfire. And the crackling and popping seemed to come from a long way off, from the same direction as a lady’s voice screaming, I remember, for someone named Harry, And the moaning. I thought it came from a woman with no shoes standing near me, but it was the wind being sucked through the trees into the fire.

Two firemen ran up to me and started yelling about fire engines. I thought they wanted to tell me something, but they just happened to stop in front of me. They were arguing about whether to call in more engines. One fellow said there was no need, and that he was going to the basement to make sure the fire was out. When he ran off, the other man asked me if I knew how to use the alarm box up the street on the corner. I said I guess you just pull it, and he told me how to break the glass and turn the crank. I must have looked like I wasn’t sure I wanted to, because the man put his hand on my shoulder and said “you’ll be saving lives, son.”

|

|